In the mid-80’s two young climbers attempted to reach the summit of Siula Grande in Peru; a feat that had previously been attempted but never achieved. With an extra man looking after base camp, Simon and Joe set off to scale the mount in one long push over several days. The peak is reached, however on the descent Joe falls and breaks his leg. Despite what it means, the two continue with Simon letting Joe out on a rope for 300 meters, then descending to join him and so on. However when Joe goes out over an overhang with no way of climbing back up, Simon makes the decision to cut the rope. Joe falls into a crevasse and Simon, assuming him dead, continues back down. Joe however survives the fall and was lucky to hit a ledge in the crevasse. This is the story of how he got back down.(Imdb)

Mountain climbing has long provided a seductive metaphor for spiritual quests, ever since Moses went up Mount Sinai and came down with the Ten Commandments.

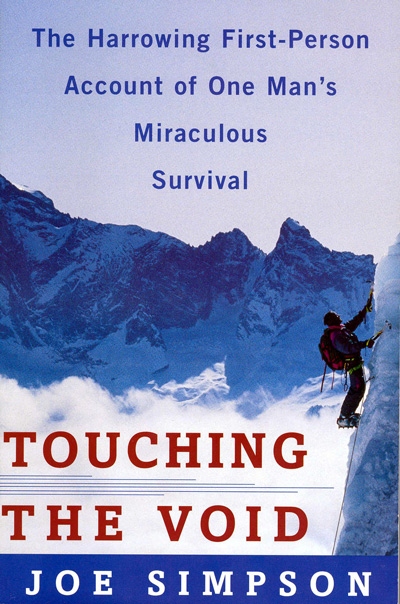

We may no longer expect explicit spiritual guidance in our mountain movies, but a film like Kevin Macdonald’s disappointing ”Touching the Void,” a British semidocumentary that opens today in New York and Los Angeles, is still very much concerned with notions of purification and transcendence, of slipping the bonds of ordinary material existence and entering a new, elevated realm of stark simplicity, elemental forces and moral clarity.

The mountain movies that were popular in Germany in the late 20’s and early 30’s, many starring Leni Riefenstahl and Luis Trenker, pointed a clear way out of the messy conflicts and confusions of the Weimar era. Unfortunately, however, they pointed to Hitler, who quickly appropriated the mountain imagery for his own propaganda ends.

In keeping with our current ideologies, the climb in ”Touching the Void” is treated less like a religious retreat than a psychological encounter session, a high-altitude group-therapy meeting that allows its two real-life protagonists, the British climbers Joe Simpson and Simon Yates, to learn important lessons about themselves and their inter-personal relationships.

With the use of staged, pseudo-documentary sequences, the film reconstructs the disastrous 1985 attempt that Mr. Simpson and Mr. Yates made on the 21,000-foot Siula Grande in the Peruvian Andes. All went well for three days until Mr. Simpson fell and drove his lower leg into his kneecap, leaving him crippled. Mr. Yates tried to lower Mr. Simpson down the mountainside with a climbing rope, but accidentally lowered him into a deep crevasse. Receiving no response from his partner, Mr. Yates was faced with a terrible choice: either to stay and hold on to the rope, at the risk of being eventually pulled into the ravine by Mr. Simpson’s body weight, or to cut the rope and try to save himself.

While the actors Brendan Mackey (as Mr. Simpson) and Nicholas Aaron (as Mr. Yates) recreate the climb on camera (with the help of climbing doubles), clambering through locations that range from the actual Peruvian mountain to Mount Blanc in the Alps, the genuine Mr. Simpson and Mr. Yates narrate their adventures from an unidentified cozy, warm place just off screen. Because we already know the two men will survive, suspense is at a minimum; the film is more concerned with the awful suffering they endured, tortures both mental (as Mr. Yates struggles with the decision to cut the cord) and physical (as Mr. Simpson finds himself in the pit of an ice cave, barely able to crawl and with no obvious way out).

This is compelling stuff, but there is something deeply distracting in the use of recreated material. Mr. Macdonald, the director, imitates a raw, video-based cinéma vérité style, but fairly often places the camera in locations that would be inaccessible to a cameraman on the actual expedition (for example, when Mr. Simpson falls into the crevasse, the camera crew is already there to meet him).

Just as Mr. Simpson falls into the physical hell of the mountain’s cavernous innards, so does Mr. Yates confront the moral hell of being forced — or so he believes — to sacrifice his partner in order to save himself. The lesson of ”Touching the Void” is that both experiences not only can be survived, but also can be an occasion for what the daytime talk shows call ”personal growth.” Having come through, having touched the void and been touched by it, Mr. Simpson and Mr. Yates are shown as elevated spirits, with a new sense of what is important in their lives and what is not. It is apparently not only the church that now produces saints but also extreme sports as well.

http://www.nytimes.com/movie/review?res=9B01E1D61039F930A15752C0A9629C8B63

For someone who fervently believes he will never climb a mountain, I spend an unreasonable amount of time thinking about mountain-climbing. In my dreams my rope has come lose and I am falling, falling, and all the way down I am screaming: “Stupid! You’re so stupid! You climbed all the way up there just so you could fall back down!”

Now there is a movie more frightening than my nightmares. “Touching the Void” is the most harrowing movie about mountain climbing I have seen, or can imagine. I’ve read reviews from critics who were only moderately stirred by the film (my friend Dave Kehr certainly kept his composure), and I must conclude that their dreams are not haunted as mine are.

I didn’t take a single note during this film. I simply sat there before the screen, enthralled, fascinated and terrified. Not for me the discussions about the utility of the “pseudo-documentary format,” or questions about how the camera happened to be waiting at the bottom of the crevice when Simpson fell in. “Touching the Void” was, for me, more of a horror film than any actual horror film could ever be.

The movie is about Joe Simpson and Simon Yates, two Brits in their mid-20s who were determined to scale the forbidding west face of a mountain named Siula Grande, in the Peruvian Andes. They were fit and in good training, and bold enough to try the “one push” method of climbing, in which they carried all their gear with them instead of establishing caches along the route. They limited their supplies to reduce weight, and planned to go up and down quickly.

It didn’t work out that way. Snowstorms slowed and blinded them. The ascent was doable, but on the way down, the storms disoriented them and the drifts concealed the hazard of hidden crevices and falls. Roped together, they worked with one man always anchored, and so Yates was able to hold the rope when Simpson had a sudden fall. But it was disastrous: He broke his leg, driving the calf bone up through the knee socket. Both of them knew that a broken leg on a two-man climb, with rescue impossible, was a death sentence, and indeed Simpson tells us he was rather surprised that Yates decided to stay with him and try to get him down.

We know that Simpson survived, because the movie shows the real-life Simpson and Yates, filmed against plain backgrounds, looking straight on into the camera, remembering their adventure in their own words. We also see the ordeal re-enacted by two actors (Brendan Mackey as Simpson, Nicholas Aaron as Yates), and experienced climbers are used as stunt doubles. The movie was shot on location in Peru and also in the Alps, and the climbing sequences are always completely convincing; the use of actors in those scenes is not a distraction because their faces are so bearded, frost-bitten and snow-caked that we can hardly recognize them.

Yates and Simpson had a 300-foot rope. Yates’ plan was to lower Simpson 300 feet and wait for a tug on the rope. That meant Simpson had dug in and anchored himself and it was safe for Yates to climb down and repeat the process. A good method in theory, but then, after dark, in a snow storm, Yates lowered Simpson over a precipice and left him hanging in mid-air over a drop of unknowable distance. Because they were out of earshot in the blizzard, all Yates could know was that the rope was tight and not moving, and his feet were slipping out of the holes he had dug to brace them. After an hour or so, he realized they were at an impasse. Simpson was hanging in mid air, Yates was slipping, and unless he cut the rope they would both surely die. So he cut the rope.

Simpson says he would have done the same thing under the circumstances, and we believe him. What we can hardly believe is what happens next, and what makes the film into an incredible story of human endurance.

If you plan to see the film — it will not disappoint you — you might want to save the rest of the review until later.

Simpson, incredibly, falls into a crevice but is slowed and saved by several snow bridges he crashes through before he lands on an ice ledge with a drop on either side. So there he is, in total darkness and bitter cold, his fuel gone so that he cannot melt snow, his lamp battery running low, and no food. He is hungry, dehydrated, and in cruel pain from the bones grinding together in his leg (two aspirins didn’t help much).

It is clear Simpson cannot climb back up out of the crevice. So he eventually gambles everything on a strategy that seems madness itself, but was his only option other than waiting for death: He uses the rope to lower himself down into the unknown depths below. If the distance is more than 300 feet, well, then, he will literally be at the end of his rope.

But there is a floor far below, and in the morning he sees light and is able, incredibly, to crawl out to the mountainside. And that is only the beginning of his ordeal. He must somehow get down the mountain and cross a plain strewn with rocks and boulders, so that he cannot walk but must try to hop or crawl despite the pain in his leg. That he did it is manifest, since he survived to write a book and appear in the movie. How he did it provides an experience that at times had me closing my eyes against his agony.

This film is an unforgettable experience, directed by Kevin Macdonald (who made “One Day In September,” the Oscar-winner about the 1972 Olympiad) with a kind of brutal directness and simplicity that never tries to add suspense or drama (none is needed!) but simply tells the story, as we look on in disbelief.

We learn at the end that after two years of surgery Simpson’s leg was repaired, and that (but you anticipated this, didn’t you?) he went back to climbing again. Learning this, I was reminded of Boss Gettys’ line about Citizen Kane: “He’s going to need more than one lesson.” I hope to God the rest of his speech does not apply to Simpson: “… and he’ s going to get more than one lesson.”

http://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/touching-the-void-2004