Simin wants to leave Iran with her husband Nader and daughter Termeh. She has already made all the necessary arrangements. Nader, however, is having second thoughts. He is worried about leaving behind his father, who is suffering from Alzheimer’s. For this reason he decides to call off the trip altogether.

As a result of Nader’s decision, Simin decides to sue for divorce at the family court. When her request is rejected, however, she refuses to live with Nader, moving instead into her parents’ home. Termeh decides to stay with her father, hoping that her mother will soon come back to live with them.

Nader finds it difficult to cope with the new situation – not least because it turns out to be so time-consuming. And so he hires a young woman named Razieh to look after his father. This young woman is pregnant and has accepted the job without her husband’s knowledge. One day, Nader arrives home to find that not only has his father been left alone, he has also been tied to a table! When Razieh returns, a blazing row ensues, the tragic consequences of which not only shatter Nader’s life, but also the image his daughter Termeh has of her father. (Mubi)

“A Separation” and “The Hunter.”

BY ANTHONY LANEJANUARY 9, 2012

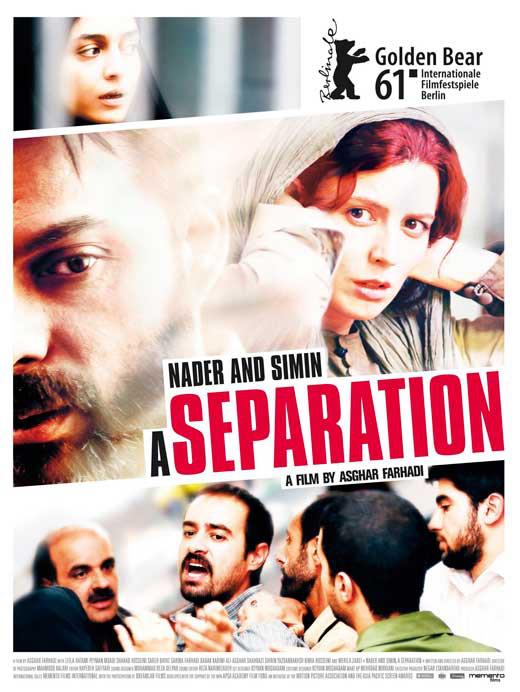

Leila Hatami and Peyman Moadi play an Iranian couple, in “A Separation.”

Who is being addressed, at the start of “A Separation”? We see two people, middle-class Iranians named Nader (Peyman Moadi) and his wife, Simin (Leila Hatami), facing the camera and discussing their possible divorce. Simin plans to leave the country and make a life abroad, but Nader wants to stay and raise their only child, an eleven-year-old girl called Termeh (Sarina Farhadi), in Iran. He has no wish to split; he wants to preserve things as they are. The couple do not hate one another, and Simin describes her husband as a “good, decent person,” but for some profound reason—a reason that is never spelled out in the movie, but that we gradually come to grasp all too well—she desires another existence. That is why, in the beginning, they look in our direction; notionally, they are pleading with a magistrate, because we hear his voice as he quizzes them, but they are speaking, with equal fervor, to us. I felt like answering back, “You talkin’ to me?”

I would love to claim that, almost two hours later, and after hearing the rights and wrongs of the case, I was able to offer sound and impartial advice, but “A Separation,” though in many respects a cramped domestic drama, yanks us to and fro with a fierce and spacious energy. You feel for almost everyone involved, yet you don’t quite know what to think, and there is something strangely exhausting in watching the most minor events—a tetchy gesture, a chance remark—set off what should be a ripple but turns out to be a shock wave. The writer and director, Asghar Farhadi, has thus created the perfect antithesis of a crunching disaster flick, such as “2012,” which was all boom and no ripple.

The initial impact, in “A Separation,” comes when Simin goes to stay with her family, either for good or by way of a trial run. Termeh remains with Nader, an arrangement that would work fine if it were not for his father, who lives with them and suffers from Alzheimer’s. Nader arranges for a carer named Razieh (Sareh Bayat) to spend the day with the old man; Razieh has a two-and-a-half-hour commute just to reach them, and she needs to bring her young daughter, Somayeh (Kimia Hosseini), with her. Oh, and Razieh is pregnant, although whether Nader has noticed her condition is open to debate. Inviting Americans to give up their winter nights for the sake of Islamic marital disputes is a tough sell, but, if audiences can be press-ganged into this movie, what they will find is a nourishing blend of the distant and the utterly familiar; anyone struggling to cope with parents in failing health, or with the guilty pressure of hiring others to look after them, will know exactly what this movie is about, while gazing in perplexity as Razieh, alarmed by the fact that the elderly father has soiled his pants, makes a phone call in search of religious advice. “If I change him, will it count as a sin?” she asks. Gravely, her little girl looks on. “I won’t tell Dad,” she says.

One day, the old fellow, left unattended, wanders into the street. Razieh locates him, to her relief, and we cut to a merry scene of adults and children, safe at home, playing a game of table football. Panic over. The next day, though, when Nader returns from work, he finds his father tied to a bedstead and Razieh nowhere to be seen. Panic back on, and this time there is no respite; when she appears, there is a scuffle, which concludes with Razieh being pushed out of the apartment, falling, and miscarrying. Nader is charged with the murder of an unborn child, and is briefly imprisoned before being bailed; he countercharges, citing his father’s maltreatment at Razieh’s hands, and, before we know it, the air is thick with wounded pride, demands for blood money, and lives on the brink of collapse. Accusations are levelled not in the ceremonious rigor of a court but in a dingy office, with the irate plaintiffs standing up and leaning over the desk of a judge, the better to hammer home their case. The judge is too harassed to be grand, and I liked the sight of him wearily dipping a lump of sugar into his glass of tea, and clearly thinking, Spare me these folk.

The miracle of “A Separation” is that it doesn’t spare any of its characters, nor does it seek to indict them. It is a democratic portrait of a theocratic world. Farhadi’s evenhanded tone recalls the approach of the great Maurice Pialat, in France, but there are strains of piety and patriarchy here with which Pialat seldom had to grapple. What frightens Razieh, for example, who is fully garbed in the chador, is that her husband, an unemployed hothead by the name of Hodjat (Shahab Hosseini), will discover what kind of job she has taken, and her fear is well founded. “I should sue you for working for a single man we don’t even know,” he says, not joking, once her secret is revealed, and we are forced to tilt our assumptions away from the egalitarian and toward a world where seemliness and modesty, virtues long lost to us, trump what we read as natural rights. Western instincts should steer us onto the side of Simin, whose head is lightly scarved but who also wears bluejeans, and yet there is something no less compelling in the calm, bespectacled mien of Termeh, who chides her mother with an essentially conservative truth: “If you hadn’t left, Dad wouldn’t be in jail.”

Not yet in her teens, Termeh—played by the director’s daughter—is the most studious presence in the film, and the least flappable by far. In a more progressive society (and here is a further irony to savor), she would make a terrific judge. During the climactic showdown, in a room filled with older men, she exchanges glances with Somayeh, who is half her age, and in that exchange there simmers, already, a well of bewilderment and exasperation at adult folly. Farhadi—unlike his compatriot and fellow-director Jafar Panahi, who is currently serving six years in prison, and is banned from making films for two decades—may be tolerated by the Iranian regime, but, if I were one of the country’s cultural commissars, the look that passes between those two young females might easily trouble my conscience, or my sleep. Grownups, in “A Separation,” are forever observing each other through open doorways, or panes of glass—a hint of permanent blockage that is rounded off by the final, heartbreaking shot of the movie, with both parents screened by partitions and their daughter walking heedlessly between them. Youth is a clearer witness of the world; through Somayeh’s eyes, we glimpse the bare and motionless legs of the sick old man, and, later, the shackled feet of a nameless prisoner, seated in the corridor outside the courtrooms, awaiting God knows what justice. If man is everywhere in chains, does it really matter, to a child, that he was born free?

http://www.newyorker.com/arts/critics/cinema/2012/01/09/120109crci_cinema_lane