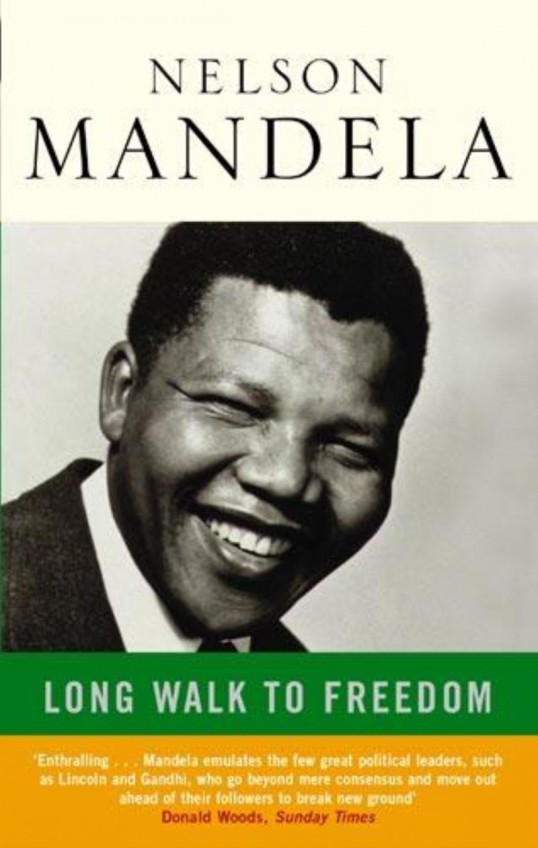

Nelson Mandela is a South African lawyer who joins the African National Congress in the 1940s when the law under the Apartheid system’s brutal tyranny proves useless for his people. Forced to abandon peaceful protest for armed resistance after the Sharpeville Massacre, Mandela pays the price when he and his comrades are sentenced to life imprisonment for treason while his wife, Winnie, is abused by the authorities herself. Over the decades in chains, Mandela’s spirit is unbowed as his struggle goes on in and beyond his captivity to become an international cause. However, as Winnie’s determination hardens over the years into a violent ruthlessness, Nelson’s own stature rises until he becomes the renowned leader of his movement. That status would be put to the test as his release nears and a way must be found to win a peaceful victory that will leave his country, and all its peoples, unstained. Written by Kenneth Chisholm

theguardian.com, Sunday 8 September 2013

It’s barely five minutes before the woman starts to wail on the soundtrack. Young men in terry-towels run through the long grass. The sun brushes the lens. He dives into the river a boy, emerges fully-formed as a world leader.

A Long Walk to Freedom lays out the legend ofNelson Mandela in grand, sonorous style. It presents a portrait of the South African freedom fighter that is shot for spectacle. This is a life heavy with significance, pitted with great speeches, backed with swooning orchestration that will climb to an emotional peak just as he addresses the crowd.

Idris Elba plays Mandela from his early days as smoothie lawyer, through his recruitment by the ANC to his arrest, imprisonment and eventual release. Elba makes a convincing statesman – he has the stature, can dummy the gravitas. His take on the icon is respectful and deft. Winnie is played by Naomie Harris, who charges the character with a revolutionary zeal.

The film rushes through Mandela’s life and times. Johannesburg, Sharpeville, Robben Island, freedom. It’s a tick-box check-list of things you should know about the man. An Encarta Encyclopedia article laid out on an epic scale. Time is contracted (we spend 30 minutes in prison; Mandela got 27 years), the greatest hits are rolled out, but there’s nothing that embraces the idea that life makes a man and informs his politics. The day-to-day is lost in the bluster.

It’s tough capturing a life so significant on screen. He revolutionised his country, but it was a long struggle with marginal victories. The film overcompensates. It bellows at you. Tells you apartheid was bad by placing champagne-sipping whites on a balcony and black people down on the streets below. It pumps in the period detail, drops in chunks of news footage to back up its importance. In reality Mandela forced change through by plugging away, by persisting in a long, frustrating struggle. The pace of change was achingly slow. It’s hard not to feel that there’s something in that that’s fundamentally uncinematic.

http://www.theguardian.com/film/2013/sep/08/mandela-long-walk-to-freedom-review-toronto

By STEPHEN HOLDEN

November 28, 2013

Hard moral decisions weigh heavily. And in “Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom,” Justin Chadwick’s stately screen biography of Nelson Mandela, the British actor Idris Elba conveys the agony as well as the nobility of Mr. Mandela’s quest for South African racial equality. Much of that pain is suppressed rage at the cruelty and injustice of apartheid. As Mr. Mandela looks beyond the fury of the moment and calculates the cost of urging violence, you sense his frustration at having to make the only reasonable choice and taking the high road.

Idris Elba, left, and Naomie Harris in “Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom,” based on Nelson Mandela’s autobiography.

Mr. Elba doesn’t look much like Mr. Mandela. He is considerably beefier. But he has the same sharp, hyper-alert gaze that acknowledges the world’s horrors while looking above and beyond toward a humanitarian ideal. He also captures Mr. Mandela’s distinctive accent with an uncanny accuracy. Mr. Elba is completely convincing as a natural leader with a ferocious drive. He makes you feel the almost unimaginable personal price Mr. Mandela paid by spending 27 years in prison, separated from his family and the anti-apartheid movement on an island off Cape Town. His lowest moment comes when he is forbidden to leave the island to bury his eldest son.

The performances of Mr. Elba and of Naomie Harris — who plays his wife Winnie, a volatile firebrand whose simmering anger can erupt at any moment — give a crucial human dimension to this streamlined, panoramic, would-be epic. The Mandelas are the only significant roles in a movie in which everyone else, including white South African leaders, is a bit player.

“Long Walk to Freedom” sustains the measured, inspirational tone of a grand, historical pageant. Events that are worth films of their own are compressed into a sweeping, generalized history. Gripping, dynamically choreographed scenes of street violence are harrowing but short, as the story hurtles forward at breakneck speed.

If the lack of specifics about politics is frustrating, how could it be otherwise? Mr. Mandela’s biography and South African history are so rich and inextricably linked that it is impossible to reduce it to a nearly two-and-a-half-hour movie without it feeling rushed and incomplete. “Winnie Mandela,” Darrell J. Roodt’s recent much inferior film, in which Mr. Mandela made only brief appearances, had the same problem.

Still, to their credit, Mr. Chadwick (“The Other Boleyn Girl”) and the screenwriter, William Nicholson, who adapted the script from Mr. Mandela’s autobiography, have created a movie with the flow and grandeur of a traditional Hollywood biopic. “Long Walk to Freedom” barely glosses Mr. Mandela’s youth. We meet him as a teenager in his Xhosa village completing a ritual initiation into manhood.

Minutes later, he is a dashing hot-shot defense lawyer and amateur boxer, whose first wife, Evelyn, leaves him because of his womanizing. He meets his match in Winnie, and they are immediately aware of themselves as a power couple bound together in a common struggle for racial equality.

Mr. Mandela’s dalliance with violence leads to his arrest and sentence of life imprisonment on Robben Island, where he breaks rocks in a quarry. The movie speeds through his prison years, taking just enough time to show the diabolical ways that punishment is meted out and small privileges extended. When he and his fellow African National Congress leaders arrive there, they are obliged to wear shorts. He wages a successful campaign for the prisoners to be given long pants, a symbolic but small victory. That’s how the movie picks and chooses its humanizing moments, and there are enough to keep its tone from seeming stuffily reverent.

“Long Walk to Freedom” warms up once Mr. Mandela is released from prison, warily reunites with Winnie and negotiates an end to apartheid with the white power structure. The compelling scenes of the Mandelas, no longer youthful, bitterly disagreeing over policy and separating, are so powerfully acted that every accusatory glance exchanged by the couple conveys accumulated years of struggle and sacrifice. Intransigently radical, Winnie Mandela endorsed retaliation against black South Africans who collaborated with the apartheid regime. One scene shows a young man about to be burned alive. During this final third, the film comes the closest to shedding its lofty airs.

Mr. Elba’s towering performance lends “Long Walk to Freedom” a Shakespearean breadth. His Mandela is an intensely emotional man whose body quakes in moments of sorrow and whose face is stricken with a bone-deep anguish. The carefully chosen words in his eloquent declarations of principle, spoken with gravity and deliberation, are deeply stirring.

“Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom” is rated PG-13 (Parents strongly cautioned) for scenes of intense violence, sexual content and strong language.